Tom

gives an update on gerrymandering and the courts with, of course, some data.

Last week a panel of federal judges did something highly

unusual: they told the state of North

Carolina that the method they had used to draw congressional district lines exhibited “invidious

partisan intent” in maximizing the chances for Republican overrepresentation in

the U.S. House of Representatives, and literally sent them back to the drawing

board. The State Assembly, which

controls the process, was given three weeks to redraw those district lines in a

fairer way; the court said they, too, would prepare new districts, and

if the state failed a second time, the court would mandate the use of its own

method.

The courts have a long history of disliking gerrymandering. Like pornography, they “know it when they

see it” (as Justice Potter Stewart famously said), but, also like pornography,

they have trouble coming up with a standard by which to determine when it has

crossed the line to become “unconstitutional.” After all, simply drawing equal-sized circles

will not ensure that each district has roughly 711,000 voters in it (the U.S. population

as of the 2010 Census divided by the number of seats in the House), and it is,

of course, very common for like-minded people to live near each other. So determining which districts have been

drawn in a biased manner is not an easy exercise.

But the North Carolinians made it easy on the courts. In what amounts to an admission of guilt, North

Carolina redistricting chief Rep. David Lewis stated the following: "I think

electing Republicans is better than electing Democrats. So I drew this map to

help foster what I think is better for the country." And when asked why he drew the map with the

goal of the GOP winning 10 of the state’s 13 districts – obviously unbalanced in this true "battleground" state -- Lewis said "because I do not believe it's possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and two Democrats." Willy Sutton could not have given a more direct and damning reply. (Sutton is the gentleman who, when asked why he robbed banks for a living, said with disarming clarity "because that's where the money is.")

Let’s illustrate this “invidious

partisanship” with some numbers and maps.

The chart below shows that, overall (the purple line), in North Carolina the GOP totaled 2.4

million statewide votes across 13 elections for the House in 2016, while the

Dems garnered 2.1 million votes, a relatively close 53% to 47% margin. Had House seats been apportioned simply on

this overall vote, the GOP would have earned seven seats to the Democrats’ six. But because the map was drawn so cleverly, to

maximize each GOP vote and minimize each Dem vote, those Dem votes were largely

shoved into three districts, the 1st, 4th and 12th,

where the Dems won handily, siphoning off votes from the other districts, which

the GOP won, also handily.

2016 Votes (000)

|

2016 Vote %

|

|||

NC District

|

GOP

|

DEM

|

GOP

|

DEM

|

1

|

101

|

238

|

29%

|

69%

|

2

|

219

|

167

|

57%

|

43%

|

3

|

215

|

104

|

67%

|

33%

|

4

|

128

|

276

|

32%

|

68%

|

5

|

205

|

146

|

58%

|

42%

|

6

|

206

|

141

|

59%

|

41%

|

7

|

210

|

134

|

61%

|

39%

|

8

|

188

|

131

|

59%

|

41%

|

9

|

192

|

137

|

58%

|

42%

|

10

|

220

|

128

|

63%

|

37%

|

11

|

229

|

128

|

64%

|

36%

|

12

|

114

|

232

|

33%

|

67%

|

13

|

197

|

154

|

56%

|

44%

|

Total State

|

2,424

|

2,116

|

53%

|

47%

|

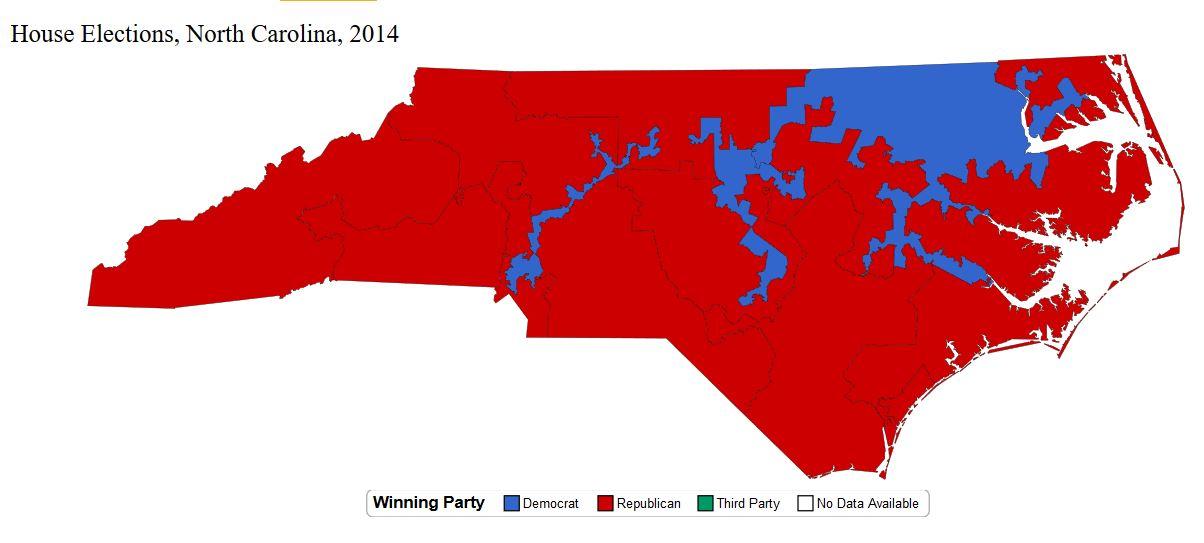

And the map below shows how they did it. By stringing together a collection of Dem

strongholds (in blue) with true “salamander” creativity, the GOP strengthened

their neighboring districts. (‘Gerrymandering”

is, of course, a portmanteau of its original inventor, Massachusetts Governor and

Founding Father Elbridge Gerry, and the salamander-esque district shapes he was

fond of creating to favor his party.)

So: Democratic

voters in North Carolina have been cheated out of fair representation in

violation of their First Amendment rights, according to federal judges. We will find out how much representation soon enough, but below is a “hypothetical”

outcome based on a “fairer” map, in which the Dems would have picked up at

least two more seats and possibly a few more.

No salamanders in this map.

Of even greater import regarding gerrymandering is the case before the Supreme Court, which will be decided in this Court term, and likely announced in late June when all the major cases are usually decided. The Court has already heard oral arguments (last October) in gerrymandering cases brought by Democrats in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania (the cases have been combined) that involve gerrymandering at the state legislature level, in which the GOP has secured outrageous majorities beyond realistic hope of ever bring “flipped.”

The Court has taken the case because a standard has been

introduced to guide determination of whether or not there is gerrymandering –

the “holy grail” of gerrymandering opponents.

If they can convince the Court of the validity of the standard, then the

Court will rule in favor of the Democrats, and maps nationwide will have to be

reassessed against this standard.

What is this mystical standard? It is called “The Efficiency Gap” and it a

mathematically-based calculation that exposes, essentially, how gerrymandered

states waste more votes for the

aggrieved party. Here is the explanation

of it, by its creator, a professor of the University of Chicago named Nicholas

Stephanopoulos (no relation to George).

“The efficiency gap is simply the difference between the parties’

respective wasted votes in an election,

divided by the total number of votes cast. Wasted votes are ballots that don’t

contribute to victory for candidates, and they come in two forms: lost

votes cast for candidates who are defeated, and surplus votes cast

for winning candidates but in excess of what they needed to prevail. When a

party gerrymanders a state, it tries to maximize the wasted votes for the

opposing party while minimizing its own, thus producing a large efficiency gap.

In a state with perfect

partisan symmetry, both parties would have the same number of wasted votes.

Suppose, for example, that a state has five districts with 100 voters

each, and two parties, Party A and Party B. Suppose also that Party A wins four

of the seats 53 to 47, and Party B wins one of them 85 to 15. Then in each of

the four seats that Party A wins, it has 2 surplus votes (53 minus the 51

needed to win), and Party B has 47 lost votes. And in the lone district that

Party A loses, it has 15 lost votes, and Party B has 34 surplus votes (85 minus

the 51 needed to win). In sum, Party A wastes 23 votes and Party B wastes 222

votes. Subtracting one figure from the other and dividing by the 500 votes cast

produces an efficiency gap of 40 percent in Party A’s favor.”

I ran the numbers in North Carolina and, as it

turns out, in the 2016 House election North Carolina had a 39% efficiency gap

in the GOP’s favor, nearly identical to the gap found by Stephanopoulos in his

hypothetical example.

Veteran court watchers believe that, once

again, this could all come down to the ubiquitous swing Justice Anthony Kennedy. Kennedy wrote over a decade ago that he

believed gerrymandering was unconstitutional under the First Amendment, and, in

the oral arguments, his questioning of the defendants seemed pretty tough. But it will all come down to whether he finds

the “Efficiency Gap” standard to be persuasive.

If he does, and is joined by the liberal

wings of the Court (as expected) the Court will thus overturn the Wisconsin and

Pennsylvania schemes. However, they may

not enforce a remedy there or anywhere in time for the midterms. They could peg it to the normal redistricting

efforts that occurs after the next Census, which would be in 2020.

In addition, note that the GOP lead in the

House cannot be attributed solely to gerrymandering. But there is little doubt that, because of

many states like North Carolina, such a verdict would be welcome news for the

Democrats and would have a material favorable impact on their electoral hopes. In the meantime, we’ll see what happens in

North Carolina on January 24 when the Assembly returns with their

new map.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Leave a comment