Tom

reflects on 1790, 2010 and 2017.

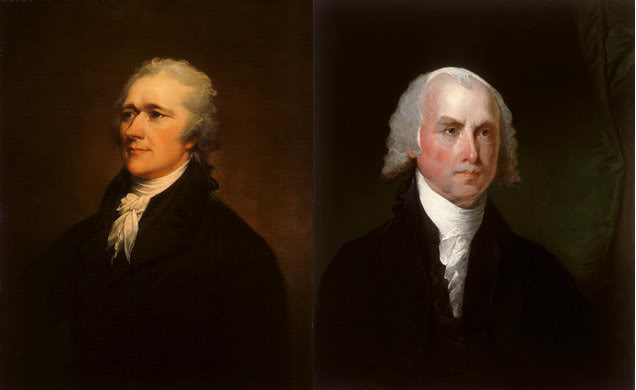

Alexander Hamilton was not very

happy. Hamilton had just delivered his

opus, a report on the credit situation of the United States, and what to do

about it, to the very first Congress. The

report was requested by Congress not long after George Washington had appointed

Hamilton to be the first Treasury Secretary, and was widely anticipated. Hamilton, in typical fashion, went far beyond

the assignment, and delivered, essentially, a blueprint for how to achieve his

vision of a strong, centralized U.S. government, replacing the ineffectual

government under the Articles of Confederation.

Among his principal recommendations was the assumption by the new

government of all state debts, which then amounted to a whopping $25 million.

Hamilton was unhappy because his

intellectual partner, James Madison, had just launched a broadside attack on

Hamilton’s report, a critique that dumbfounded Hamilton. Just two years before, the pair had written

80 of the 85 Federalist Papers that were so instrumental in securing passage of

the Constitution, thereby replacing the Articles and setting our nation on its unified

course. Madison was the strongest voice

in Congress, and his blessing, which Hamilton took for granted, was crucial to

passing Hamilton’s plan. But Madison, it

turned out, was wary of a strong, centralized government, and he knew the assumption

of states’ debts would irrevocably establish the federal government’s

preeminence over the states.

Hamilton was unhappy because his

intellectual partner, James Madison, had just launched a broadside attack on

Hamilton’s report, a critique that dumbfounded Hamilton. Just two years before, the pair had written

80 of the 85 Federalist Papers that were so instrumental in securing passage of

the Constitution, thereby replacing the Articles and setting our nation on its unified

course. Madison was the strongest voice

in Congress, and his blessing, which Hamilton took for granted, was crucial to

passing Hamilton’s plan. But Madison, it

turned out, was wary of a strong, centralized government, and he knew the assumption

of states’ debts would irrevocably establish the federal government’s

preeminence over the states.

And so began the battle still

being waged in Washington, DC, today over the power of the federal government. Hamilton and Madison would become

arch-enemies, Hamilton (and President Washington) favoring – to put it mildly

-- a strong, centralized government, while Madison (joined by the new Secretary

of State, Thomas Jefferson), fearing the same, and favoring states’ rights

instead. The party names have changed

since the time of the Federalists and Anti-Federalists, but the Dems and the

GOP carry on the debate.

It is hard to find an issue that better

exemplifies the two underlying party philosophies than the health care

insurance debate. The Dems believe in a strong

role for the federal government, expressed through Obamacare, which sought to

subsidize health insurance for the previously uninsured through an expansion of

Medicaid, paid for by taxing the wealthy, and requiring a commitment of all

Americans to enroll in health insurance program, the so-called mandate. The GOP considers Obamacare to be yet another

massive federal entitlement program, and for years argued for its repeal and a

return to a market-driven system, with no “forced choices” such as the mandate. Once in power, however, Trump realized that

simply “repealing” the now-popular Obamacare would leave him and the GOP open

to huge criticism, and thus announced a goal to “replace” it as well.

The divide reveals the effects of

the two philosophies in ways rarely so starkly quantified It is a pretty clear choice, and the CBO

analysis makes the trade-off clearer still.

The new Senate bill will result in 22 million fewer Americans with

health care coverage, and would save roughly $300 billion over ten years. Under the GOP plan, the more limited government

approach would give the wealthiest Americans a huge tax cut and deny coverage

to poorer and older Americans, while eliminating the mandate of insurance

coverage.

Which brings me to Ted

Kennedy. Perhaps no public official

worked harder over his career than Kennedy to expand health care coverage

(Kennedy’s and the Dem’s true goal was universal coverage via direct government

insurance, essentially Medicare for all).

How thrilled Kennedy surely must have been in 2009 to see Obamacare

moving through Congress; not universal care, perhaps, but strong enough to cut

the number of uninsured in America from 50+ million to half that. And success seemed assured, because the

Democrats controlled the Presidency and both houses of Congress, indeed they

had 60 certain votes in the Senate, enough to pass the bill without a single

GOP vote.

Fate would, of course, intervene,

and Kennedy would die in August, 2009, before he could cast one of those 60

votes. And a Republican, Scott Brown,

would, shockingly, win his seat. Obama

would get his bill though, and the GOP House would go on to vote to repeal it

60 more times. Obamacare in practice did

reduce the number of uninsured by tens of millions, but the Supreme Court,

while upholding (surprisingly) the constitutionality of the bill, made the states’

Medicaid expansion requirement optional.

Obamacare’s various flaws inhibited its effectiveness, and in a number

of states the number of insurers remained low.

Kennedy would not have been

surprised by Obamacare’s defects. He would have seen the bill in a clear-eyed

manner – landmark legislation that went far in achieving far greater coverage,

but with defects, in need of legislative improvement. “Never let the perfect be the enemy of the

good” he would intone; his legislative philosophy always favored passing a good-but-not-perfect

bill and then fixing it over time. In

Ted Kennedy’s Senate, this was the way it was.

But the GOP has, in seven years, refused

to follow that dictum, choosing to repeal rather than engage in the needed

fixes. And thus, now, we have the ”repeal

and replace” madness, with a Senate bill that is only slightly less “mean” (to

use Donald Trump’s own words) than its House counterpart. The fractured GOP hates the bill from both the

far right and from the moderate center, and in reality, it is a garbage bill in

all ways.

Hamilton could have predicted the

folly of “repeal and replace”. As he

said, “Whoever considers the nature of our government with discernment will see

that though obstacles and delays will frequently stand in the way of adoption

of good measures, yet when once adopted, they are likely to be stable and

permanent. It will be far more difficult

to undo than to do.” Hamilton also decried

smallminded legislators who followed their constituents rather than lead

them. He bemoaned, “The inquiry

constantly is what will please, not what will benefit, the people.”

How did Madison’s Congress

ultimately pass Hamilton’s program? In

the best political tradition, the way it has been practiced from 1790 until very

recently, a deal was cut, the first major compromise in our legislative

history. Hamilton and Madison went to

dinner at Jefferson’s house, in our young nation’s first capital in New York

City. And by the time dinner was over,

Hamilton would have his bill, and Jefferson and Madison would have what they wanted, which was that the permanent site of the capital would border their

beloved Virginia, right on the Potomac, in what would become – yes, Washington,

DC.

The GOP of the 115th

Congress (or its immediate predecessors) does not appear to be capable of doing

what Hamilton, Madison, Jefferson and Kennedy would have done – reaching a compromise

with the Dems and fixing the ACA, which would actually both please and benefit the people. The undoing is exposing the GOP’s

dysfunction, putting them in a lose/lose debacle, where passing the bill could

very well be worse than failing to pass the bill.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Leave a comment